ABOUT TEXTILES

Artists & ArtworksDescription

The techniques of dyeing and weaving fabric (senshoku) are indispensable to daily life. In Japan, these techniques are the culmination of centuries of tradition and fashion aesthetics going back to the court culture of the Heian period (794–1185), the samurai culture of the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1600), and the merchant culture of the Edo period (1603–1868).

Process

-

STEP 1Process

Japanese dyeing and weaving use three basic types of thread: silk fiber, bast fiber (e.g., ramie), and cotton fiber.

-

STEP 2

- The thread is woven into fabric.

- The thread is dyed.

-

STEP 3

- The fabric is dyed

- The dyed threads are woven to make fabric

White fabric is dyed with designs in various colors. In yūzen dyeing, a resist paste is used to draw designs. In katazome stencil dyeing, patterns are created using stencils.

Weaving is the process of interlacing vertical and horizontal threads on a loom to create fabric. Different dyeing and weaving techniques can be used to produce a variety of patterns. No matter how intricate the pattern, it is always made from an arrangement of vertical and horizontal threads.

- STEP 4 The finished fabric is used to make clothing such as kimono or obi

Artistic Techniques

Dyeing

Fabric dyeing (somemono) techniques

Yūzen dyeing

Yūzen dyeing (yūzenzome) is one of Japan’s best-known traditional dyeing processes. It involves drawing designs on white fabric with a paste resist before dyeing the fabric. First, the fabric is cut into the shape of a kimono and an outline of the design is drawn onto the cloth using the blue dye of the Asiatic dayflower (aobana), which can later be washed away without leaving a trace. A paste resist is then applied over the lines of the outline, creating masked-off areas that prevent the colors from mixing, and the design is dyed. Finally, the paste resist is washed away, leaving behind fine white lines of undyed fabric where the resist was applied. This style of yūzen is known as itome yūzen (“line yūzen”). Resists may also be applied broadly across the fabric to create designs without white lines. This style of yūzen is known as sekidashi yūzen.

Stencil dyeing

In stencil dyeing (kataezome or katazome), first a stencil is created by laying a pattern over shibugami (a durable washi paper treated with tannin) and the design is cut into the paper. The resulting stencil is used to apply paste resist to create a repeating pattern that can then be dyed.

Edo komon

Edo komon (literally “Edo small crests”) developed during the Edo period (1603–1868) as a finely detailed decoration for kamishimo, a piece of formal attire worn by samurai. Later, the style spread to commoners’ kimono as well. Historically, Edo komon is dyed using Ise stenciles (Ise katagami).

Nagaita chūgata

While Edo komon consists of fine designs applied to silk, nagaita chūgata (“long-board medium-pattern”) fabrics are made by applying larger designs to cotton for yukata (informal summer kimono) using a long board of about 6.5 meters.

Block print dyeing

In block print dyeing (mokuhanzome), a brush is used to apply dye to wooden blocks with designs carved into them.

Bingata polychrome resist dyeing

Bingata polychrome resist dyeing Bingata (“colored pattern”) is a type of paste-resist dyed fabric with polychromatic designs produced around Shuri in Okinawa prefecture. The style is characterized by vivid colors and designs with gradations or “shaded” edges. Conventionally, bingata is contrasted with paste-resist dyed fabrics in indigo monochrome called ēgata (“indigo pattern”). While the paste resists for bingata are typically applied using stencils, the patterns may also be drawn freehand.

Shibori tie-resist dyeing

For shibori tie-resist dyeing, artisans use string to tightly tie, stitch, or fold fabric to prevent the dye from penetrating parts of the cloth. Unlike yūzen dyeing, in which the dye is applied using brushes or pastes, the designs for shibori are created by immersing the cloth in dye. The bound portions remain undyed and produce pleasing color gradations. Tie-resist dyeing is Japan’s oldest dyeing technique. Over one hundred shibori techniques continue to be practiced today, including fawn spot (kanoko shibori), stitch resist (nuishime shibori), and capped resist (bōshi shibori).

Weaving

Weaving (orimono) techniques using dyed thread

Kasuri weaving

Kasuri weaving (kasuriori, “blurred weave”) is a type of ikat weaving done with threads that have been resist dyed, leaving sections of the thread undyed. The threads are then aligned and woven to create stripes, checkered patterns, or pictorial motifs.

Tsumugi silk

Tsumugi silk is woven from spun silk thread (tsumugi ito). Tsumugi is not as smooth or glossy as reeled silk, and features a simple, nubby texture.

Echigo jōfu

Echigo jōfu (“Echigo fine cloth”) is a fabric with a long history, made from the fibers of the perennial plant ramie (choma, or karamushi). The fabric is woven on a simple backstrap loom, which allows the weaver to adjust the tightness of the warp (vertical threads) using a strap around the weaver’s waist. The design is created by arranging the alignment of the weft (horizontal threads). The woven cloth is then softened by kneading the fabric in hot water, and naturally bleached by laying it out over snow on a sunny winter day. The finished colored fabrics take on a more subdued tone, while the white fabrics are bleached a brighter white, resulting in a high-quality fabric for summer kimono.

Saga brocade

Saga brocade (Saga nishiki) is a woven fabric that uses dyed silk threads for the weft (horizontal threads) and finely cut strips of washi paper called tategami for the warp (vertical threads). The paper strips are grouped and lifted apart using a bamboo tool called a shed stick, and the silk thread weft is passed through the gap to create the desired pattern. Repeatedly running the weft through the gaps between the paper strips results in a fabric with beautiful, orderly patterns.

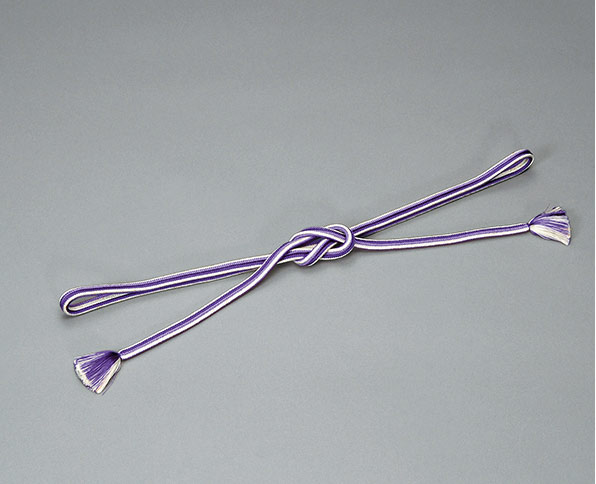

Kumihimo braided cords

Kumihimo braided cords are made by gathering dozens of threads into separate bunches and then braiding the bunches together into a single cord. For centuries, kumihimo cords have been important articles for tying and binding. Today, kumihimo cords of many different patterns are worn with kimono as obi jime (a decorative girdle tied around the obi of the kimono).

Embroidery

In Japan, embroidery (shishū) dates back to the Asuka period (592–710). Dyed threads are handsewn into fabric with a needle to create designs.

Hakata brocade

Hakata brocade (Hakata ori) is a woven textile produced around the Hakata district of Fukuoka, Fukuoka prefecture. The weave employs thousands of closely packed warp threads, which almost entirely hide the weft. Representative patterns, consisting of warp threads, include stripes and “offertory motifs,” such as Buddhist thunderbolt scepters (vajra) and “flower plates” for Buddhist flower-scattering ceremonies.

Ra silk gauze

Ra silk gauze is a type of open leno weave in which sets of vertical warp threads are intertwined around the horizontal weft threads, producing an open fabric. Unlike plain sha gauze weaves, in which simple pairs of mated warp threads are crossed and intertwined as though to form a single warp, ra gauze weaves employ intricate systems of intertwining warps. The patterns are further complicated by also intertwining the weft threads. Ra gauze is characterized by large, open meshes with decorative patterns. The technique was transmitted from China around the seventh century and enjoyed great popularity from the eighth to tenth centuries (Nara–early Heian periods).

Monsha figured gauze

Monsha “figured gauze” combines sections of plain and leno weaves to produce an open fabric with decorative motifs. Sha is a type of leno or cross weave in which spiraling pairs of mated warp threads are twisted around consecutive weft threads to produce a light, transparent fabric with an open weave structure.

Fūtsū double weave cloth

Fūtsū double weave cloth (fūtsū ori) is a type of compound weave that uses two different sets of colored warp threads. The figuring on both faces of the resulting double-layered cloth have an inverted color relationship. Fūtsū (lit. “wind passes through”) refers to the opening between the two layers of cloth.

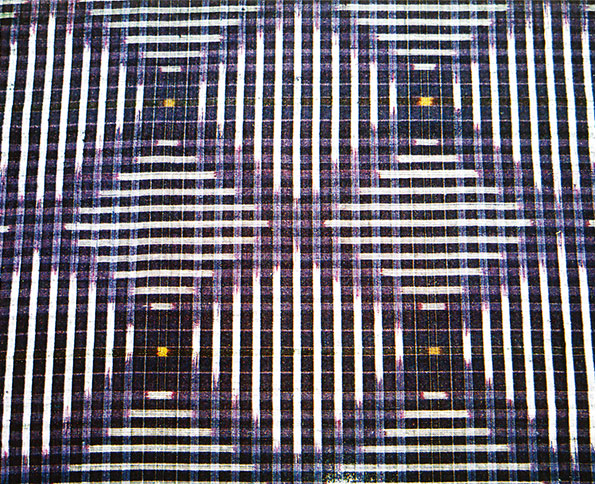

Kurume kasuri

Kurume kasuri is a type of ikat woven fabric produced near Kurume in Fukuoka prefecture. An artisan first creates a fabric design and then resist-dyes bundles of threads, tying them in special arrangements (kasuri kukuri) to create white-reserve patterns on the dyed thread. The individual threads are then woven together to create the final design, producing motifs with characteristically blurry edges. Kurume kasuri is a nationally designated Important Intangible Cultural Property.

Textiles Artists

Main Production Areas

Nishijin brocade

Nishijin Brocade is a silk fabric produced mainly in the north western part of Kyoto City, Kyoto Prefecture. Its distinctive feature is the thread-dyeing technique where the threads are dyed prior to weaving. This gives the fabric a luxurious and profound finish.

Kaga textiles

Kaga Yuzen is a textile produced mainly in Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture. Compared to Kyo Yuzen, it has deep, subdued colors and realistic designs with plant and flower patterns.

Kurume traditional resist-dyed textiles

Kurume Kasuri is a cotton textile produced mainly in Kurume City, Fukuoka Prefecture. It is known for the blurred and smudged hand woven patterns. Kurume Kasuri is one of the three major kasuris of Japan, together with Bingo Kasuri and Iyo Kasuri.

Ojiya chijimi textiles

Ojiya Chijimi is a ramie textile produced around Ojiya City, Niigata Prefecture. It is known for its wrinkled texture called shibo, made by using tightly twisted threads. It is perfect for making light and breezy kimonos for the hot and humid summer in Japan.